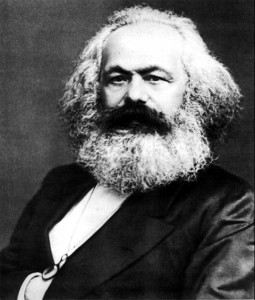

“On the 14th of March, at a quarter to three in the afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think.” Those were the words of Friedrich Engels at the funeral of his close friend and creative collaborator, Karl Marx. The funeral took place in Highgate Cemetery in London. The year was 1883 and there were less than a dozen mourners present. The world had yet to be exposed to the work of the man laid to rest in that small ceremony. But it would only be a few short years before the established political order would tremble at the name of Karl Marx and – in some places – be ripped down entirely by the words that flowed from his pen.

It’s not easy to write about Marx. Everything that could possibly be said about the man and his ideas has already been said a thousand times over. He has been raised to the status of a secular god by some, while others have done their best to cast his memory into the fiery pit of hell. A powerful case can be made – if one were so inclined – to label Marx as the single most influential philosopher in history… right up there with the semi-mythological figures of the Sacred Texts of the world. At the same time, there are those who would argue that the historical transformations attributed to his works had more to do with the lust for power of those acting in his name, than anything Marx himself wrote. Just as the words of Nietzsche were ripped from their original context and violently twisted into an ugly justification for German fascism, so the words of Marx have been brutalised almost beyond recognition to fit the ambitions of tyrants. Of course, some would say that a utopian philosophy inevitably leads to tyranny. And despite the protestations of some Marxists, there’s little doubt that Marxism contains a utopian vision within it.

Karl Marx was born into a relatively wealthy family in the oldest city in Germany, Trier, a couple of miles on the German side of the Germany-Luxembourg border and only 20 miles from the border with France. His upbringing in this uniquely Franco-German environment exposed the young Marx to an eclectic mix of influences and he enjoyed an education that was extremely liberal for the time. Indeed his high school was stormed by police in his second year after accusations that the liberal humanist philosophy of the headmaster had crossed the line into outright sedition. By his late teens, Karl Marx was something of a rebel and gained a reputation as a party animal. Despite this he was awarded his PhD by the age of 23 – his thesis, an attack on theology as a source of knowledge about the world – and was writing for a radical newspaper in Cologne. Soon however, he fell foul of Germany’s censorship policy and fled to Paris where he met Friedrich Engels and would commence one of the most influential collaborations in history.

Just as had happened in Germany, Marx’s writing fell foul of the French authorities who accused him of attempting to incite rebellion and he was expelled from the country. His arrival in Brussels was not met with much enthusiasm from the authorities and he was permitted to remain only a few short years before he’d worn out his welcome. Using a large portion of his inheritance after his father’s death to purchase arms for a radical Belgian workers union turned out to be the last straw. Significantly, however, his time in Belgium did produce one of his seminal works, The Communist Manifesto.

Marx would spend the rest of his life in relative poverty. After expulsion from Belgium he returned briefly to Germany but was quickly forced into exile once more and Paris would not take him. So it was that he arrived in London in 1849 where he would spend the rest of his life. Here he would write arguably the most significant book in the history of political and economic philosophy, Das Kapital.

With the possible exception of Sigmund Freud, it’s difficult to think of anyone whose work has been so influential and yet so radically misunderstood as Karl Marx. Yes, the road to utopia invariably gets diverted into authoritarianism, but to suggest that Soviet Stalinism or Mao’s Cultural Revolution embodied the vision of Marx is nonsense of the highest order. Even the most famous of Marxist quotes are invariably taken so far out of context as to render them misleading at the very least… Religion is the opium of the people has become a cliché. Yet few are aware that the full quote subtly alters the message that Marx sought to convey…

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

Marx was certainly not defending religion – which he saw as an illusion – but he was pointing out that it was an entirely natural reaction to a world in which the vast mass of humanity was being oppressed by economic forces over which they have no control and by kings and presidents who used their power to maintain this oppressive environment. Thus, said Marx, the criticism of Heaven turns into the criticism of Earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law, and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics. Marx never suggested that the abolition of religion was in any way desirable within the existing social order. Such a thing would be almost barbaric; to brutally stamp out “the sigh of the oppressed creature”. The point was to remove the oppression… the need for that sigh… not simply to silence those in pain.

Over the years, the fortunes of Marxism have risen and fallen. Despite almost every implementation of Marxist ideas becoming a perversion of those ideas, there were few areas of 20th century culture that did not bear his fingerprints. Marx virtually invented the social sciences. Art, economics and politics all found themselves radically transformed by his ideas – as well as by the reactions against his ideas. During the 1990s, as the dust settled on the communist regimes in Eastern Europe and China’s Communist Party began its journey towards Authoritarian Capitalism, the theories of Marx were declared obsolete. The End of History had finally arrived, we were told, and far from winding up in Marx’s socialist utopia, it was capitalism that had triumphed.

But now, as we watch the edifices of capitalism start to shake. As rampant inequality, resource depletion and environmental catastrophe begin to undermine history’s end, suddenly those who called time on Marx are beginning to look a little premature. Only a fool would predict the crisis facing western civilisation will result in a glorious international communist revolution ushering in a new socialist utopia. Such an outcome seems suprememly unlikely from our vantage point here in March 2011. Nonetheless, Marx’s critique of capitalism; the assertion that it contains the seed of its own destruction, that it must eventually collapse beneath the weight of the greed it inevitably generates (“the most violent, mean and malignant passions of the human breast, the Furies of private interest”) and that “stock-exchange gambling” would lead to a “bankocracy”; all appear more relevant now than ever.

Despite the terrible things that were done in his name, we should remember Marx not for the actions of those who twisted his ideas to fit their own agenda. Instead we should remember him for the ideas themselves. For his belief that no man should be oppressed by another, that a better vision of society is possible if people stand shoulder to shoulder rather than eyeball to eyeball, and that humanity is capable of far more than crawling around in the filth searching for sticks with which to beat one another into submission.

WORKERS OF ALL LANDS UNITE.

[Written by Jim Bliss]

7 Responses to 14th March 1883 – the Death of Karl Marx