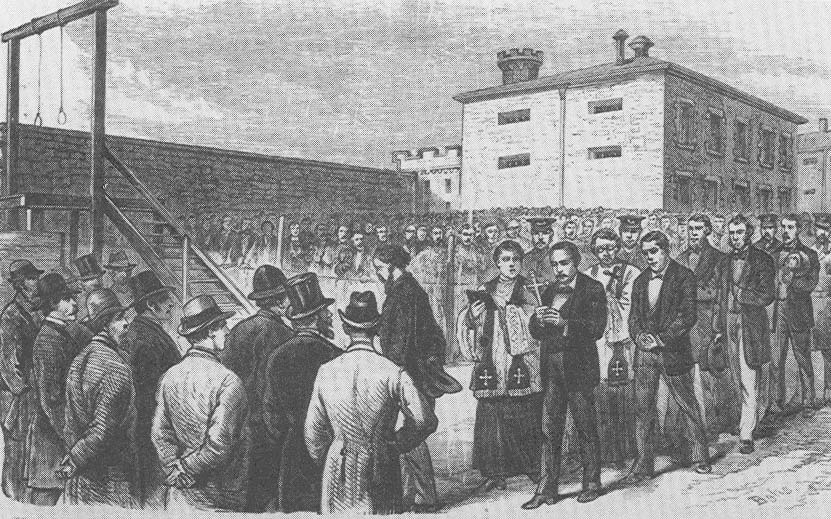

On 21st June 1877, in the anthracite-mining county of Schuylkill, Pennsylvania, ten Irish immigrant men alleged to have been members of an oath-bound secret sect of vigilantes called the Molly Maguires were hanged in what came to be known as “The Day of the Rope”. Twenty members of the group in all would be executed, following a kangaroo court that American historian John Elliot called “one of the most disgraceful episodes in the history of the bench and bar in the United States.” Oppression, exploitation, racial and ethnic bigotry, strikes and union-busting are common enough themes in the American labour movement. But the story of the Molly Maguires and the ruling class’s attempts to destroy these Irish workers is so especially contemptible it has achieved legendary status. Did the so-called Molly Maguires – said to be part of the Ancient Order of Hibernians – even exist?

Molly Maguire might have been a real woman or she may have been a myth. Whatever the truth, she served as an Irish talisman against agrarian oppression in 1840s Ireland. In the wake of famine and land seizures, her symbolic spirit was relocated to the United States – along with two million Irish emigrants. But for these new hopefuls in the land of opportunity, “Irish Need Not Apply” regularly appeared alongside “Help Wanted” ads. For many, the only option was the brutal coalmines of Pennsylvania. The conditions were perilous, the pay pitiful. Workers lived in homes owned by the mining companies, forced to buy all their supplies from company-owned shops at inflated prices, leaving them in debt and enslaved to their employers.

In spite of hazardous conditions that regularly led to death tolls in the hundreds, the mining industry fiercely resisted unionisation. In 1874–1875, after Pennsylvanian coal-miners went on strike, the Molly Maguires allegedly began sabotaging mining equipment and facilities – detonating bombs along rail lines, roads and bridges so that mine owners couldn’t bring in replacement workers. The ruling class called it terrorism, others called it resistance. Industrial leader Franklin B. Gowen called in the notorious Pinkerton Detective Agency, who hired an Irish American to infiltrate the miners. Over the course of two years, James McParlan – under the alias James McKenna – befriended the Irish community, all the while gathering the evidence that would eventually hang twenty men.

The trials – conducted in an atmosphere of religious and social bigotry fuelled by the national press – were a travesty of justice, and a surrender of state sovereignity. The defendants were arrested by the private police force of Franklin B. Gowen, the same industrial magnate who’d financed the Pinkerton operation. They were convicted on the evidence of an agent provocateur, supplemented by the confessions of several informers who turned state’s evidence to save their own necks. Defense witnesses were blacklisted, evicted from their homes, cut off at the company store and in some cases imprisoned. Catholics were barred from the Jury, while many of the selected jurors were so anti-Irish that they pre-determined a guilty verdict. Most of the prosecuting attorneys worked for the railroads and mining companies. And Franklin B. Gowen himself appeared as the star prosecutor at several trials – his courtroom speeches rushed into print as popular pamphlets. Even by nineteenth-century standards, the arrests, trials, and executions were flagrant in their abuse of judicial procedure and their flaunting of corporate power. Yet only a handful of dissenting voices were to be heard, chiefly those of labour radicals. The Philadelphia Public Ledger encapsulated the national feeling when it previewed Black Thursday as a “day of deliverance from as awful a despotism of banded murderers as the world has ever seen in any age.”

Following the executions, nothing more was heard of the Molly Maguires. No admission of vigilantism was ever offered from the Irish American coal-mining community and, if the Molly Maguires ever existed, they left no evidence of themselves. The only accounts were written by those with hostile interests.

Thirteen years after the Day of the Rope, the unions prevailed and the United Mine Workers was created. Unable to cope with the prospect of treating workers well, Franklin Gowen committed suicide. Several years later, evidence surfaced that suggested Gowen had been behind many of the acts of sabotage attributed to the Molly Maguires. In 1979, a posthumous pardon was granted for the Mollies, with Governor Milton Shapp denouncing Gowen’s “fervent desire to wipe out any signs of resistance in the coal fields.”

All Pennsylvanians, he said, should pay tribute to “these martyred men of labor.”

Pingback: On the cusp of a revolution | The "Great" American Novel: 1900-1965