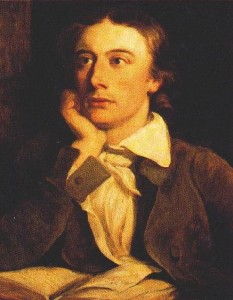

Today we reflect on the brief but luminous life of John Keats – struck down by tuberculosis on this day in 1821 at the age of 25. Little known and lowly regarded in his lifetime, the dying poet – resigned to eternal obscurity – insisted his grave in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome be left anonymous and his epitaph read only: “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.” Some three decades after his death, however, the world would begin to recognise that John Keats had in fact been one of the greatest English poets to have ever lived. In the three years of his poetic career, he published only fifty-four poems, in three slim volumes and a few magazines. But with his prodigiously rare gift and mystically sensual awareness of nature, love and life, he greatly advanced the poetic form – and, in his six legendary Odes – perfected it.

The tragic, heart-rending tale of John Keats’ short life is one that all but equals the poignancy of the poems themselves: the early loss of his parents; cruelly cheated out of his inheritance; the abandonment of medical studies to devote his life instead to poetry; the abject poverty that followed; a beloved younger brother’s prolonged death from tuberculosis; the cruel and savage attacks on his work; a fiery love affair with Fanny Brawne never to be consummated; his own battle with the dreaded “White Plague”… all of which led inexorably to his embittered, premature death in Rome.

“Nothing is finer for the purposes of great productions than a very gradual ripening of the intellectual powers,” wrote John Keats to his brother on January 23rd 1818. What riches might he have brought forth had his own already-formidable intellectual powers been allowed to ripen with maturity? We can only lament the loss of such promise. But whilst mourning what might have been is inevitable when contemplating John Keats, on this anniversary of his death, let us instead celebrate the extraordinary, elevated ouevre he bestowed upon us. The beautiful Endymion – the target of such vicious and erroneous criticism. The abandoned epic Hyperion. The visionary theory of Negative Capability. A canon of some of the most compelling and insightful letters – by any literary figure – on the nature of the creative process. And, most of all, the Odes… those six explosions of perfect genius composed in quick succession in his “annus mirabilis” of 1819.

Percy Bysshe Shelley declared in Adonais, his famous elegy to Keats, that the young poet would be part of “the white radiance of Eternity.” Nearly two centuries after his death, the poetry of John Keats is indeed forever luminous.

2 Responses to 23rd February 1821 – the Death of John Keats