It was the spring of 1968, the “year that rocked the world”. In America, the anti-Vietnam movement was intensifying, stirred by the Tet Offensive and My Lai Massacre. The women’s rights movement was mobilising. And Black Power and the Black Panthers had unseated the non-violent civil rights movement – Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination serving as the final ironic nail in its coffin. Today we’re remembering a seminal event in that epochal year.

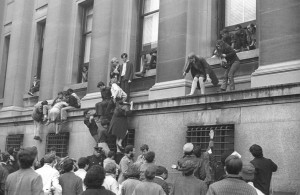

On April 23rd 1968, students at New York City’s elite Columbia University held a demonstration which escalated into a week-long occupation of five campus buildings before police moved in. 712 students were arrested, while over 100 were injured during the forcible eviction. In the wake of such a heavy-handed response from the police, who’d acted on the orders of the university trustees, students called a strike and the campus shut down for the rest of the semester. The Columbia upheaval was the loudest and most reported university protest in a landmark year of global unrest, and is widely seen as the pivotal moment of radicalization of hitherto politically indifferent students.

So just what were these privileged Ivy Leaguers so pissed off about? And what happened?

A month earlier, the Columbia chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) had learned of the university’s complicity in the Vietnam War through its affiliation with the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA). When SDS petitioned Columbia’s president to sever the university’s ties with this military research group, six of its members were placed on disciplinary probation. The April 23rd rally was ostensibly in support of the “IDA Six”. The demonstrators, numbering in the hundreds, attempted to storm the library but were held off by security guards, and proceeded instead to Morningside Park – where construction was underway on a 10-storey Columbia gymnasium on public land. Local Harlem residents – primarily poor blacks – were to have only limited use of the facilities, and would be expected to use a separate basement entrance. Just three weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the gym was seen as a repugnant symbol of the university’s racist contempt for its neighbours, and the angry students – both white and black – began tearing down the fence around the site. Pushed back by the police, the students returned to campus to “liberate” the main hall – taking the university’s dean as their hostage. Over the next six days – against a backdrop of tense negotiations, communal living, news cameras, supportive telegrams from Chairman Mao, folk songs, Black Power activists and the hoof clops of the massing NYPD – four more buildings were seized in what had become a mammoth struggle between the New Left and the Old Order. For although the protest superficially centred around three specific issues, these demands were merely symbolic of the far broader issues of racism, imperialism and authoritarianism. Said Columbia SDS president (and future Weatherman) Mark Rudd:

“Any particular issue we raise probably can’t change things all that much, but changing people’s understanding of society, getting them to understand the forces at work to create the war in Vietnam, to create racism: this is the primary goal of radicals. And the harvest of this planting will not be seen in this year when we gain a modicum of student power, not in ten years…but sometime in the future when this understanding of capitalist society bears fruit in much higher level struggle.”

The students ultimately won their goals: the gym was never built, Columbia’s weapons research contract was terminated, and amnesty was granted for most demonstrators (with the notable exception of Rudd and a few other ringleaders). There was the additional victory of the not incidental resignations of Columbia’s president and provost. But the most significant implications of the 1968 occupation and strike extended far beyond Columbia. Campuses around the world exploded. From Paris and Prague to Tokyo and Mexico City, students took to the streets – and for a while it seemed that revolution was just a shot away. Before the year was out, however, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated, the Prague Spring was crushed by Soviet tanks, the Chicago police violently beat protesters at the Democratic Convention and Richard Nixon was elected President. But, for a brief moment at least, these committed and highly organised students proved that protest is our essential duty and change is possible.

Today’s young revolutionaries would do well to study closely the tactics of and lessons from Columbia’s extraordinary Class of 1968.

4 Responses to 23rd April 1968 – the Columbia University Student Protest