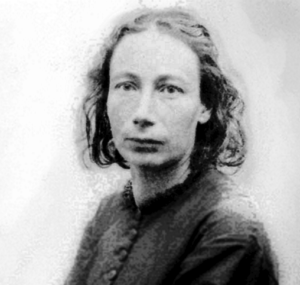

Born on this day in 1830, at the dawn of an extraordinary revolutionary age, Louise Michel was the Transcendent Revolutionary – an extraordinary French woman whose ideals and displays of generosity to the Parisian poor existed at such a hands-on level that she was known even in her own lifetime as ‘’The Sister of Charity’. For her selfless devotion to France’s revolutionary cause, and for the religious manner in which she lived, Mme. Michel earned another portentous nickname ‘The Red Virgin of Montmartre’ – Christlike in her compassion for the downtrodden, a teacher to the ignorant and the destitute, an ardent helper of minority races, this illegitimate daughter of a servant and a dissolute nobleman – her high ideals aloof from the possibilities of failure – caused such constant and chronic problems for the French authorities that they eventually exiled her to a distant island. This is Louis Michel: so high falutin different from the herd that she was even raised in a castle. Her outpourings of poetry, her many musical compositions, her fascination for horticulture, her need to learn obscure languages: all these things point directly to a busy bee obsessed always with the cross pollinations of Culture – not just her own culture, but all those with which she made contact. To Louise Michel, every culture belonged to and was a part of its people. To wrestle control of that culture from the stultifying interpretations of the Top Knobs was her goal.

So what made a saint of this lifelong contrarian? What makes a saint? In each case, it’s their determination to do what is necessary, by any means necessary. Canonisation comes much later – everyday pains-in-the-arse get ahead, but Visionary Moaners will not go unheard! Such was Louise Michel.

Mme. Michel was 41 when she first exploded on to the political scene as the famed heroine of the Paris Commune – that momentous turning point when the working classes briefly seized power for the first time and, for 72 elevating days, proceeded to form their own pioneering socialist government. This trailblazing experiment set about reinventing society, introducing free meals and housing for the poor, increasing workers’ wages, and proclaiming freedom of the press. Unlike most women in revolutionary history, Michel did not play a supporting role. Indeed, simply describing Louise Michel’s daily actions explain how capably she shattered all gender assumptions. Chairing political and vigilance committees, appropriating churches for use as schools, co-steering the iconoclastic feminist movement, fighting in military uniform alongside her male Communards, even dragging the wounded to safety as an ambulance nurse – hands-on, sleeves rolled up, in the thick of it always. Other Communards often displayed centuries-old prejudices – not Louise Michel. Against even the wishes of her comrades, she demanded that prostitutes be welcomed into the Commune’s nursing corps: “Who has more right than these women, the most pitiful of the old order’s victims, to give their lives for the new?”

The French government eventually sent in the army who, during the infamous ‘Bloody Week’, massacred an estimated 20,000 Communards. Forced afterwards to stand trial, in a stunningly defiant speech, Louise Michel demanded her equal right to the same death sentence as her male comrades: “Since it seems that any heart which beats for freedom has the right only to a small lump of lead, I demand my share. If you are not cowards, kill me!”

But the government was unwilling to make a martyr of France’s legendary “Red Virgin”. Instead, this French heroine was exiled to New Caledonia, a distant Pacific island. Even here, however, her beatific nature could not be suppressed as she made botanical experiments while crystallising her political ideas – she would become an Anarchist. And while fellow Communard prisoners displayed hostility and racism towards the indigenous Kanaks, Mme. Michel instead befriended them, learned their language and customs, then helped to organise their independence movement – to eliminate central power everywhere remained always her mantra.

When after seven years the exiled Communards were granted an amnesty in 1880, Louise Michel received a hero’s welcome upon her return to Paris. For the rest of her days she would continue to agitate and educate, her fiery speeches and eloquent writings giving voice to the plight of the have-nots. For this, she still suffered constant harassment, even further imprisonment, but never did she abandon her dedication to improving the lives of others. And while we can be certain no church will ever canonise her, she is nevertheless the Saint of Anarchism. Bless her!